Adding gs_usb Hardware Timestamping to Kernel Module

I recently had to check a CAN node was providing a cyclic message within a 10% threshold of the defined period. Logging the messages, it appeared that it was slipping by as much as 25% at times.

In addition to a hardware specific logger, I was debugging with a SocketCAN ‘gs_usb’ compatible tool and wanted to ensure that the host OS was not introducing any timing error.

SocketCAN candump has a flag -H to enable hardware timestamps; timestamps from the capturing device rather than the host OS stamping upon receipt (software timestamps). When the tool provides a timestamp, it should be much closer to when the transceiver actually received the message1. Timestamps provided by the host OS may be inaccurate due to preemption by a higher priority task before the USB packet is retrieved; it’s the time it was popped from the USB queue so the period that the OS got around to this is included. More on the Linux kernel net timestamping options

My USB CAN tool of choice is and my Entree board, which uses candleLight firmware. The problem was that adding the -H flag resulted in zeros. Digging into the firmware, I saw that it does support sending timestamps as part of the gs_usb packet but that the Linux kernel module did not yet use it.

The module that required changing was gs_usb. Contributing to something like Linux is probably the most intimidating but also rewarding things to do in open-source. It’s not something that is easy to jump into and so opportunities to actually change some code are few. Additionally, whilst it is mirrored on GitHub the collaboration process is still mailing list based so it’s not just a simple case of opening a PR in a nice web GUI!

To my benefit, one of the contributors to candleLight is also a maintainer of the CAN modules and was very helpful in pointing me in the right directions. It also meant I already had someone on-board to do the final merge request. Reading the excellent documentation first also got me a long way before submitting to the mailing list. In all, the process took around four months from identifying the problem, patching then finally it being merged and release as part of Kernel 6.1. Here it is in the Linux commit log (GitHub mirror). It’s actually quite involved as the timestamp sent is a tick count from a 32 bit timer, which requires a worker to maintain a datetime relative timestamp.

The process really epitomised why I love open-source:

- Was quickly able to pin point what was missing and where by looking at the code. That’s not possible with closed-source tools.

- The feature wasn’t present but I wanted it and it would benefit others to add it.

- Good documentation meant setting up a development environment was quick and abiding to contribution guidelines easy.

- Existing experienced contributors aided but hopefully were not burdened by a new feature being developed by someone else.

- It all happened asynchronously, remotely and without any meetings in four months to being included in one of the World’s most used software.

Usage and Difference Illustration

One can check the timestamping capabilities of a tool using ethtool and a candleLight will now report support for hardware RX and TX.

> ethtool --show-time-stamping can0

Time stamping parameters for can0:

Capabilities:

hardware-transmit

software-transmit

hardware-receive

software-receive

software-system-clock

hardware-raw-clock

PTP Hardware Clock: none

Hardware Transmit Timestamp Modes:

on

Hardware Receive Filter Modes:

all

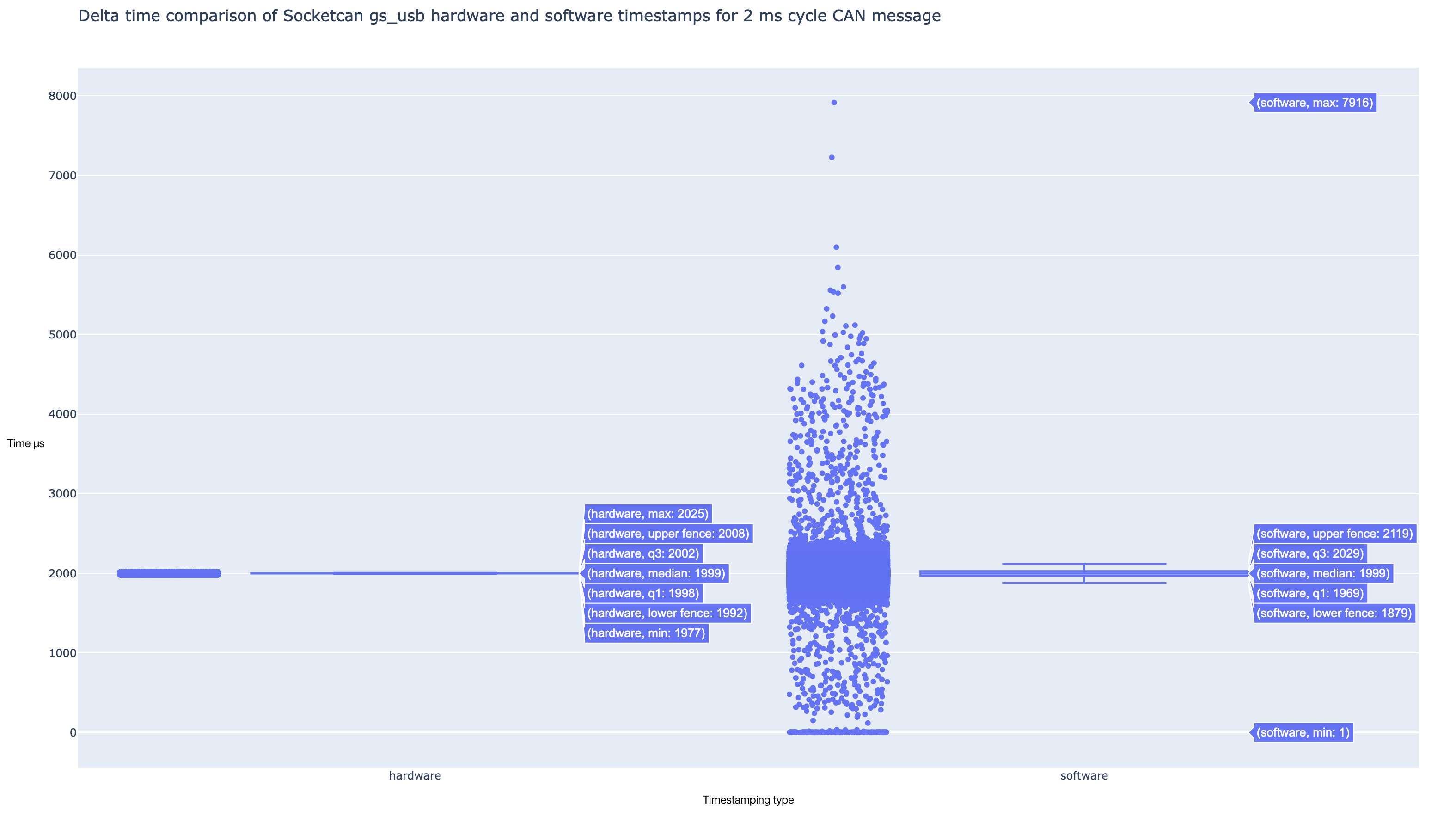

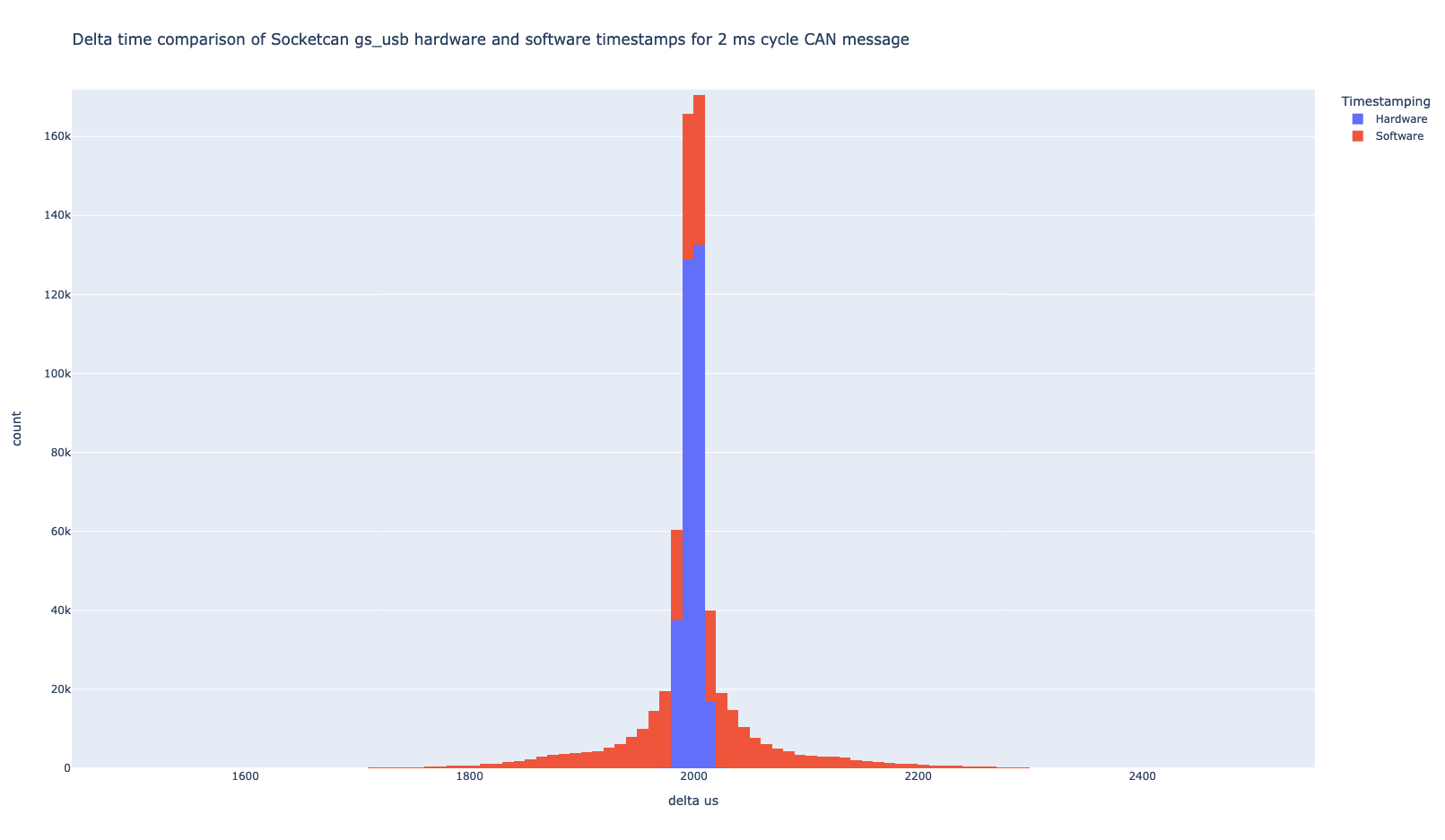

During the development and following the released 6.1 kernel with the updated module, I ran some tests to illustrate the difference between using software and hardware timestamping. Using a STM32F4 device (external oscillator with 72 MHz main clock) configured with the sole job to send a CAN message every 2 ms from the SysTick ISR, I captured on the same interface with both candump can0 -l -H (hardware) and candump -l (software). The plots and statistics are generated using a quick Python script.

Click the graphs to view live but downsampled versions (too slow and large with all datapoints).

The box plot at standard zoom is not ideal because the spread is so different between the two. It does visually highlight how much more reliable hardware timestamps are over software ones however.

The box plot at standard zoom is not ideal because the spread is so different between the two. It does visually highlight how much more reliable hardware timestamps are over software ones however.

One can see that a software timestamp > n * 2 ms will result in the following n timestamps appearing to be ~0 ms due to the system actually popping all the packets that arrived in the n * 2 ms period and stamping them all in quick succession.

One can see that a software timestamp > n * 2 ms will result in the following n timestamps appearing to be ~0 ms due to the system actually popping all the packets that arrived in the n * 2 ms period and stamping them all in quick succession.

One can see there is a pronounced difference in the accuracy of the timing; the software timing makes the device appear to be unstable. I did intentionally load the system and it was running in a virtual machine so is a worse case perhaps. It is still clear that if one is doing timing specific tests, hardware timestamps are very important if not critical2.

# Hardware Timestamps

Max: 2025 µs

Min: 1977 µs

Stddev: 6.8 µs

Variance: 46.6 µs

Largest percentage slip: 1.25%

# Software Timestamps

Max: 7916 µs

Min: 1 µs

Stddev: 113.1 µs

Variance: 12789.7 µs

Largest percentage slip: 295.8%

-

In candleLight firmware, it’s when the gs_usb packet is queued - not perfect but good enough for most use cases. The resolution is limited to 1 µs. ↩︎

-

On a non-real-time kernel at least - it would be interesting to test with a real-time one. They should be more stable but could not beat the accuracy of the hardware supplied ones. ↩︎